![]() Sons of the Desert - Script to Screen II

Sons of the Desert - Script to Screen II

In a living arrangement probably unparalleled in the history of Hollywood (a place for which, it is increasingly clear, God owes Sodom and Gomorrah an apology), Ruth moved into the Palm Drive house with Stan prior to the first of their three marriages, but insisted on being chaperoned! No "living in sin," she said. "That would just kill mother."

Not a problem!

Stan's pals Baldy and Alice Cooke, both of whom appear in SONS OF THE DESERT, lived with the couple -- and watched them fight -- until they were officially wed. Or at least thought they were. The Cookes couldn't return to their apartment for three months!

"I lost all my friends," Alice Cooke told Fred Guiles, "and Baldy used to have to go home every day and feed the cat and bring me a dress every day. But oh the fun we had! My God!"

On January 24, 1934, cheerless vice-president Henry Ginsberg, on behalf of Hal Roach Studios, Inc., wrote quite officially to "Dear Mr. Laurel:

"Upon your return to the Studio on the 24th of January, 1934, you have informed us that you have been unable to work on account of the condition of your health....

"We further understand from you that, on account of your health, it will be impossible for you to render services pursuant to the contract of employment between us dated January 7th, 1930. By reason thereof, we avail ourselves of the provisions of the contract relating to your disability ... and the contract shall be suspended, due to such incapacity ... commencing with and subsequent to January 16, 1934.

"We have stated to you then, and we reiterate it now, that we are desirous that you resume the rendition of the services provided for and specified in such agreement in existence between us at the earliest possible moment, and of which resumption we shall be glad to receive notice from you.

"We, indeed, regret the incapacity so occasioned by the condition of your health."

That is, the unspecified condition of Mr. Laurel's health.

Definition of "subterfuge": any plan or trick in secret to escape something unpleasant. Having to negotiate alimony and property settlements, for instance, qualify as activities which might be unpleasant.

Ollie to Mrs. Hardy in reel number three, SONS OF THE DESERT: "I wonder what could be the matter with me?"

Mrs. Hardy: "Well, it looks to me like a severe nervous breakdown. You've gone all to pieces, and it happened so suddenly."

Ollie: "Probably that terrible argument we had the other night caused it all. Ohhhhhhh! Oh!"

With SONS OF THE DESERT in wide release, on January 31, 1934 Hal Roach's friend, Hearst columnist Louella O. Parsons, broke this story: "The sad-faced Stan Laurel is growing sadder by the minute. He is taking a suspension on his Hal Roach contract and at the moment is receiving not one cent in salary. The rotund Oliver Hardy is sad, too, because he is out of a partner and unless Stan has a change of heart, Wallace Beery and Raymond Hatton will replace the famous comedy team in BABES IN TOYLAND.

![]() "The Laurel peeve isn't aimed at Oliver, nor is it aimed at his boss, Hal Roach. It's leveled, as we hear, against his ex-wife. At the time of the divorce, Laurel practically turned everything he owned over to his wife and, in return for his freedom, also agreed to give her a large part of his salary.

"The Laurel peeve isn't aimed at Oliver, nor is it aimed at his boss, Hal Roach. It's leveled, as we hear, against his ex-wife. At the time of the divorce, Laurel practically turned everything he owned over to his wife and, in return for his freedom, also agreed to give her a large part of his salary.

"Realizing that he wasn't working for himself, Stan asked for an alimony compromise, which was refused him. So he has decided his health isn't robust enough for him to continue working in strenuous comedies."

Bebe Daniels, Hal Roach, and Doc Martin, the husband of Louella Parsons, all shared the same January 14 birthday. Their natal anniversaries were celebrated together in high style every year for decades. Almost certainly the source of information in Parsons' column was Hal Roach.

Ironically, the villainess in the piece is alleged to be Lois Laurel. Although he would become increasingly ambivalent towards his star comedian, Roach was then protecting both his own interests, and also his friend, Stan Laurel. In fact, Roach always believed the worst professional and personal mistake of Stan Laurel's life was the dissolution of his first marriage, to Lois. "She called his bluff," Roach explained in 1977. "He pushed her into that divorce. His success and his ego had gone to his head. Lois wasn't going to take any more of his temperament and inconsiderate behavior. She'd had enough. Yet she was the love of his life. When he came to his senses, he tried to get her back. She wouldn't take him back. He never recovered."

Later in life Roach was much closer to Lois, than to Stan Laurel. Lois had represented him in contract negotiations with the studio, and Roach came to respect her enormously. During the studio's first spring break following SONS OF THE DESERT, Roach wanted Lois to accompany him and his wife, Margaret, to Europe, to help him evaluate talent! She didn't go for the same reason she declined to travel with her husband and Oliver Hardy on their triumphant tour of the British Isles in 1932 -- she was not in the best of health. Besides she had to care for young Lois. Roach offered to provide a nurse. That's the kind of esteem he held for Lois Laurel.

Plus for decades after Stan Laurel left the studio, Roach would call Lois for advice on doctors, dentists, any number of things and for the rest of his life. In 1990 at the Catalina Island centennial celebration honoring Stan Laurel, Roach made a point of asking Stan's daughter to be sure and thank her mother, again, for a stock tip given Roach half-a-century before. It was a utility stock, Pacific, Gas and Electric, or PG & E, and Roach was still reaping the rewards of its healthy dividends!

Curiously wives Lois and Ruth were very friendly through the years. On the occasion of Lois's subsequent birthday during the initial year of Ruth's romance with Stan, Ruth encouraged him to take Lois out to dinner and celebrate! Daughter Lois and Ruth were always quite fond of each other, with Lois becoming the executor and principal beneficiary's of Ruth's estate upon her death in 1976.

On February 12, Louella Parsons carried another installment in the ongoing saga of sagging connubial bliss: "Stan Laurel is still among the missing. He just cannot make up his mind whether to return to England, to stop payments on his alimony, stage a reconciliation with his wife or make a settlement with her. That's all right for him, but it's tough for Hal Roach, who finds the plump Oliver Hardy without his screen partner.

"Hal is optimist enough to believe Stan will come to his senses and return to the Roach studios. If he doesn't, Hardy will go it alone, with Patsy Kelly as his leading lady. But there won't be any attempt to team Hardy, for the present at least."

Miss Parsons' source, once again, was undoubtedtly Hal Roach. Her line about Stan "coming to his senses" presaged the exact thought Roach drew upon when looking back on Laurel's mistaken judgement, so many years later in 1977, as quoted above. It was probably the same way he originally explained the situation to Louella Parsons in 1934.

Ollie to Stan in reel number three, SONS OF THE DESERT: "Don't you understand that this is only a subterfuge -- to throw the wives off the track so that we can go to the convention?"

Stan to Ollie: "Oh, then you're not goin' to the mountains."

Ollie: "Of course not."

The proposed pairing of Hardy with marvelous comedienne Patsy Kelly was no idle threat. A year later when Stan Laurel was again in trouble at the studio, a new domestic series called THE HARDY FAMILY (also referred to as THE HARDYS) was announced. It pre-dated the same-named and wildly successful M-G-M series starring Mickey Rooney which began with the 1937 film A FAMILY AFFAIR. The first Hardy family would have consisted of Oliver Hardy and Patsy Kelly as parents of Our Gang's Spanky McFarland! Patsy Kelly never failed to steal every film she appeared in, and Spanky McFarland's role model at the time was Oliver Hardy! A fascinating script running 43 pages and written by Hal Roach himself exists to substantiate concrete plans for the unit. It would have been a wonderful new franchise for the studio.

![]() Also, in February of 1934 it was true Laurel had offers to make personal appearances in London, Paris and other European cities if he were to move back to England. Shown the second Louella Parsons column on the matter in 1989, Hal Roach again used the word "bluff" to characterize the situation, saying on that occasion, "Stan could not believe it when Lois called his bluff and left him. He only threatened to walk out of the studio and go home to England in hopes Lois would make up with him and take him back. She would not. I wish she had."

Also, in February of 1934 it was true Laurel had offers to make personal appearances in London, Paris and other European cities if he were to move back to England. Shown the second Louella Parsons column on the matter in 1989, Hal Roach again used the word "bluff" to characterize the situation, saying on that occasion, "Stan could not believe it when Lois called his bluff and left him. He only threatened to walk out of the studio and go home to England in hopes Lois would make up with him and take him back. She would not. I wish she had."

Daughter Lois Laurel has the letters from her father "pleading to go back with my mother." To no avail.

On February 16, in a story headlined "Noted Comics Not To Split," the Associated Press circulated a new development: "The persistent rumor in Hollywood that the comedy team of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy was to be split was denied yesterday by both comedians.

"Laurel, reported to have negotiated a contract for personal appearances in England and France, said he had taken a few weeks' leave from the Hal E. Roach Studios for a rest.

" 'I wouldn't think of negotiating a contract on my own hook,' said Laurel. 'I realize my value as a comedian lies in the fact that I am teamed with Hardy.'

"Hardy also said there was no impending split."

On March 8, Henry Ginsberg signed and approved a two page document drafted by Ben Shipman on behalf of Stan Laurel seeking permission for one or two days work to complete necessary retakes and added scenes for HOLLYWOOD PARTY at Metro. Without this waiver of the suspension, Laurel's strategy for defeating the expensive terms of his divorce would have been impaired. "I feel it my obligation and duty to do my best to appear (in HOLLYWOOD PARTY) and finish this work, and have so stated to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer," Laurel wrote.

Permission to complete the picture was granted and when it was previewed in Glendale on March 28, the headline in THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER read, "Laurel & Hardy Steal MGM's HOLLYWOOD PARTY: Comics Highlight Dull Musical."

So much, as usual, for what mighty Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer knew about making comedies.

Not understanding the provisions of the divorce laws, and mistakenly believing he was free to wed, the day after April Fool's Day, Stan Laurel phoned Virginia Ruth Rogers at her dress business and asked if she'd like to get married. At first she hesitated, then gave in. Just as Ollie had done so impulsively in OUR WIFE (1931), they'd elope and be married by some justice of the peace they hoped to find. In that picture, "How romantic," were the approving words of Ollie's bride-to-be, Babe London.

Laurel rounded up his chaperones Alice and Baldy Cooke (who had to be pulled off the Charley Chase picture he was appearing in, appropriately entitled ANOTHER WILD IDEA). The four of them drove to the depot in downtown Los Angeles and then travelled by train to Mexico. Stan Laurel married Virginia Ruth Rogers in Agua Caliente, Mexico, that very night, April 2, which date unfortunately preceded the official dissolution of his marriage to Lois. The couple's supposed blessed union was invalid in the state of California, their home. When this news got out, Mr. Laurel addressed the matter by assuring reporters that he and his virginal bride would not live together as man and wife -- and definitely not -- until the divorce from Lois was final, and positively terminated. As in, absolutely ended. Officially and legally. In only six short months. What married couple couldn't wait six months? How hard could that be?

Ollie to his wife in reel number two, SONS OF THE DESERT: "Wait a minute, sugar. There's no use getting excited. You're making a mountain out of a mole hill."

Stan to Mrs. Hardy: "Certainly. Li -- life isn't short enough."

Virginia Ruth Rogers stated that her first husband, deceased, had been tubercular, and asserted that their marriage had never been consummated. She was, therefore, in her words, "as close to a virgin" as Laurel was likely to find, particularly in Hollywood. Baldwin and Alice Cooke would share duties chaperoning the happy couple for only six more months.

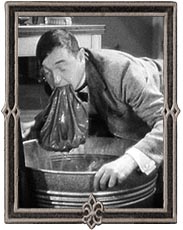

No wonder Stan was eating wax apples in SONS OF THE DESERT.

On May 7, 1934 Stan and Lois N. Laurel gave new, written instructions to Hal Roach Studios, Inc. rescinding payments of compensation to the trust in favor of direct payments in equal amounts to each of Mr. and the former Mrs. Stan Laurel.

While some of these events seemed to parallel the designs of a Hal Roach two reel comedy, the boss himself was not amused.

He was gone from the Laurel & Hardy unit, and studio, by the time SONS OF THE DESERT was made, but Oscar-winning writer-director Lewis R. Foster said of working for Hal Roach, "I really loved the man; all of us would have done anything for him. But any time you saw Roach bear down and set that granite jaw of his a certain way, it was best to find a place to hide. We all knew he'd been a boxer, a truck driver, he had forearms like Popeye the Sailor and hands the size of a grizzly. In fact he hunted wild game and there were bearskins all over his office! He could sell any idea since he had quite a magnetic personality -- which was usually how he was, easy- going -- but he could be equally intimidating the other way. So while you wanted to please the boss because he inspired you, at the same time you didn't want to displease him because you were afraid he'd kill you and skin you!"

There's a chilling prospect. Hal Roach was gregarious and well-liked. He was equally dynamic and direct. It is true that when he was displeased, his eyes and face assumed a determined glare that could cause apples to fall from trees.

Until the day he died, the entire thrust of Hal Roach's career was offering the public clean, decent, positive, uplifting family films and television programming utilizing seemingly wholesome if not virtuous talent whose private lives were models of immaculate behavior and could stand the test of any scrutiny. Nothing less. Or else. There was never any arguing about this, or anything else, with Hal Roach. The "morals clause" in everyone's contract at the studio was not there just to give attorneys something to do. Stories in the media about failed marriages, or any type of impropriety or philandering by his contract stars undermined the chaste, exemplary image of his laughter-inducing "lot of fun," and did not please him. Did not. Would not, and did not.

As SONS OF THE DESERT was being produced and distributed, the press was understandably having great fun at the expense of the studio's world-renowned comedians. Hal Roach found little to laugh at. He did find this kind of publicity was a good way to achieve maximum tension. One might have predicted all the trouble and worry would shorten his life.

On May 7, 1934 Stan and Lois Laurel notified Hal Roach Studios, Inc. that all future compensation due Mr. Laurel should be paid, in half, separately, to each of the two parties.

In the words of the Exhausted Ruler, "Whole-heartedly, unanimous!"

Or, maybe not.

Finally on June 13, 1934, following a miraculous "cure," Stan Laurel informed the studio via a single page document that he was ready to resume "the rendition of services," thus ending his self-imposed suspension.

Stan to Ollie in reel number six, SONS OF THE DESERT: "I've certainly got to hand it to you."

Ollie to Stan: "For what?"

Stan: "Well, for the meticulous care with which you have executed your finely formulated machinations in extricating us from this devastating dilemma."

Worthy of study by sociologists writing doctoral dissertations on human nature, SONS OF THE DESERT is on one level a delightful comedy, but also portrays a surprisingly complex moral diagram, the time-honored epic struggle of men versus their wives, the ethical as well as the unjust choices both sides make, and the respective consequences of their actions. SONS OF THE DESERT delineates the basic battle of the sexes. And every time the film is run, the wives prevail, showering their husbands with crockery, or intimidating them with shotguns. They win! Never changes. Each and every screening, they win, and all of it is deeply funny, thoroughly human, with a remarkable balance of comedic and deadly serious moments.

What was going on off-screen, away from the studio, during pre-production, between scenes, through post-production and worldwide release of this film was not so funny, but no less a struggle involving the film's principal stars against all the many women in their own private lives whom they loved, whom they couldn't live with, and whom they couldn't live without. What does it mean? Quoting once more the immortal words of his crew answering Billy Gilbert in Our Gang's SHIVER MY TIMBERS (1931), "We don't know, Captain."

Enumerating the marital miseries of Oliver Hardy, Charley Chase, and Stan Laurel and in trying to make sense of any of this, at least one thing is certain. In the very least, knowing some of the domestic issues complicating, even tormenting, the lives of these stars, can only enrich our appreciation of the comedy they somehow were able to bring to the screen in SONS OF THE DESERT. One wonders if making this picture was some kind of therapeutic release for them.

Hal Roach was not only a top polo player, he was also a horse racing enthusiast who had long followed the sport of kings. For several years he'd been arranging financing to seek a license from the California Horse Racing Board to build and operate a track. The week SONS OF THE DESERT was supposed to begin shooting, September 26, Hal Roach gave a luncheon at the studio for newspaper sports writers. According to the page one story in THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER, Roach "explained his plans for a race track to be chartered under the new state law." Roach was the founder and first president of the Los Angeles Turf Club, which created and controlled the racetrack renowned today worldwide as Santa Anita Park, "The Great Race Place."

Two days later trade papers and sports pages alike carried more news, including the list of film names who had applied for the $5,000 cooperative ownership-membership privilege in the proposed racetrack, some of whom were Roach's pals like producers Arthur Loew, Darryl Zanuck, and Joseph Schenck, directors John Cromwell, Frank Borzage, and Charles Brabin, and stars Robert Montgomery, Chico Marx, and Harold Lloyd. Investors who subscribed in the required amount of $5,000 to qualify as a partner, or member, reaped a small fortune.

Around the studio, Roach urged anyone who could afford it to buy stock in Santa Anita. Babe Hardy did; he needed no coaxing. Stan Laurel did not. His decision was made for him by Lois Laurel. Eventually she amassed a net worth exceeding the combined wealth of Stan Laurel and all his ex-wives, but she missed the bet on Santa Anita. Her usually thorough stock research fell short because she failed to understand that the land would be part of the business plan. Nor did Charley Chase invest, although always conscious of trying to please Roach he did manage to work horse racing into a two-reeler he made late in 1934 entitled THE FOUR STAR BORDER.

"I gave start-up shares to my mother as a gift," Hal Roach remembered. "She held on and did very well, eventually turning over the stock to my brother Jack. Babe Hardy sold his, which I advised him not to do. He dropped plenty of dough betting the horses and felt that was the way to recoup his losses. I put up plenty of money myself, betting just like a sucker, and lost most of it the same as he did! You might wager that the president of the damned place would know something about horses, but you'd lose too!"

Busy as he was launching Santa Anita, flying around the country in his plane, playing polo, and planning for the studio's gala twentieth anniversary celebration at the end of the year, Hal Roach still found time to manage development of the literary property for SONS OF THE DESERT. He saw the project as a watershed motion picture for the future of both Laurel & Hardy and the Hal Roach Studios. Which it was. His undated, untitled copy of one (incomplete) scripted incarnation of the "F-4" story that still survives today runs 42 pages and describes 78 scenes, with dialogue.

The few inscribed notes Roach made reflect concerns about the timing of scenes, the emphasis of certain plot points, and where gags were needed, as opposed to what the gags should be. With the exception of Stan Laurel, Roach was as good at devising gags as anyone at the studio, but by 1933 the scope of his attention was usually well above the task of writing comedy material. He generally delegated such work to others.

Despite the transition to feature films, with new filmmaking talent, one concept in the working methodology of the Laurel & Hardy unit remained constant. Some of the best comedy was discovered on the set, spontaneously. That explains why scenes were not shot out of order, which cost the studio more money, but resulted in better films. Here was where Stan Laurel really shined as a consummate professional, "bossing the set," as Hal Roach described it. If a scene wasn't clicking, Laurel and the writers would tear it down right there, ad-lib it, block it out, work it out. Sometimes, because Laurel was so conscientious and such a perfectionist, they would go through a scene over and over and over. More often Laurel would simply lead a discussion in something new they planned, then shoot it fresh and "hot," with no rehearsal!

What Laurel & Hardy scene in any Hal Roach film does not look real, natural and spontaneous? The rule was, the script should be followed "only if no better ideas present themselves during production." Often they did. Most often those ideas arose from the fertile brain of Stan Laurel. What we usually do not know is what those deviations from the script were. Following are some of them.

In the script, "the exhausted ruler" is called "the grand master."

The lodge room was intended to have an "atmosphere of ghostly mystery." When they are first introduced, Laurel & Hardy are already seated; their late entry which disturbs the proceedings was not scripted.

Instead of Chicago, the 487th annual convention of this really old organization was to be held in "Decago," wherever and whatever that was supposed to mean. (A "decagon," as geometry students know -- don't we all? -- is a plane figure with ten sides and ten angles.) The alleged proper noun "Decago" was used and spelled that way more than once in the script, so it was not a misprint. Possibly it was a pejorative name for Chicago arising out of the derisive slang word "dego" (meaning "Italian") during the concurrent reign of Italian mobsters such as Al Capone and his successors in the city.

The protracted confusion with the doors and doorbells outside the double bungalow was not reflected in the script. "Gags here," was Hal Roach's terse hand-written notation.

Despite all the boasting in the cab ride home about being "king of his own castle" (a line which obviously made a lasting impression on comedian Jackie Gleason), Ollie eases into the news when trying to tell his wife he'll be leaving to attend the convention. He speaks "very sweetly" to his wife, with a "languid attitude," as indicated by the script. Stan is confused by Ollie's change in demeanor, which he gets across by some intrusive comments. The script, by the way, refers always to "Babe," never to "Ollie."

"Babe pantomimes for (Stan) to shut up," the script reads, "then smiles reassuringly at his wife. Noticing her dead-pan and feeling that he isn't getting over, he decides to three-sheet for Stan's benefit, and begins to get a little tough (with) his wife."

It was always fun to speak with people who worked at the studio and hear the comedy filmmaking jargon and shorthand they used and knew, which no one else did. A "three-sheet" is a door-sized poster advertising a particular film with drawn illustrations and splashy graphics displayed outside of theaters to entice patrons inside after stepping up to the boxoffice. In this context, "to three-sheet" meant for Ollie to show-off and make a pretentious display of himself.

When Mrs. Hardy becomes exasperated, raises her voice and informs Ollie he is not going to the convention but instead to the mountains, she next storms out of the scene and slams the door with terrific force. Ollie reassures Stan, "Don't pay any attention to her. She's only clowning." All this is filmed as described, but the written account of the action called for is interesting: "A vase is thrown into the scene and hits Babe on the back of the neck. He takes it, but doesn't look back as he knows full well where it came from....He gives up and sits down."

Throughout the story Stan does plenty of dim-witted things such as when Ollie exclaims of their phony-physician scheme, "Our plan is working out great!" and Stan responds numbly, "It sure is ... only why do you want to go to Honolulu?" The indicated response that was called for: "Babe takes it in patient disgust."

What's interesting is how often lines of dialogue or action are introduced with adverbs indicating the attitude called for in delivering the line or the look -- "impatiently," "mournfully," "disgustedly," "hotly," "emphatically," "grandiloquently," "boastfully," "absent-mindedly," "sweetly," "genially," "bewilderedly," "defiantly," "anxiously," "firmly," "hesitatingly," and "dead-pan." Try and match the modifier with the film's characters. Hardy's camera-looks are most often indicated by the word "takem," and usually by "double takem." More jargon.

By page 22 in the script the convention city is now magically Chicago, rather than Decago. Roach must have understood the meaning since there are no marginal emendations.

In a sequence not included in the released film version, the ranks of parading conventioneers include a crack team of bicyclers "going through a series of intricate formations, each move cued by the blast of a whistle....Stan and Babe, resplendent in their brilliant uniforms, are riding at the head of the bicycle squad....Stan and Babe are doing circles and cross-overs and other stunts....The entire squad crashes in a tangled heap."

This elaborate sequence, where the team also becomes ensnared in a huge, long banner was deemed too risky, or too complicated, or unconvincing with whatever doubles might have been required, or just not funny, or maybe all of the above. Charley Chase had just incorporated a bicycle scene in his MIDSUMMER MUSH (1933) which could have been the genesis.

At the boisterous speak-easy, with the "celebrating lodge men and their girl friends ... acting like college kids," we learn that the character played by Charley Chase -- "Bill, a middle-aged, pie-eyed fellow" -- was evidently not written for him. This would be consistent with the (usually suspicious) pressbook story telling how Chase read the script then asked for the part. Roach wrote Charley Chase's name in the margin, but whether the casting suggestion was Roach's idea or Chase's petition remains unclear. Also "Bill" and "Texas-97" are written as two different lodge members.

As Laurel & Hardy enter the speak-easy, they are supposed to be "a little tight." And the pocketbook gag is employed at two different spots in the proceedings, instead of one.

When "Bill" phones his sister back in Los Angeles, he responds to her question, and explains about "The music? We're in a speak! Liquor -- women -- gambling! You should get a squint! And have I got a couple of pals -- Los Angeles pals! ... That ain't a bad connection, sis, we're drunk! Talk to my pal -- he's a big Son of the Desert -- no, sis -- desert: d-e-s-e-r-t! Here he is."

The Hardy household address in the script was different at 2222 Adams Way.

A scene was written for Stan and Ollie to get into an altercation resolved by two bouncers rushing in to "double-time them out" of the speak-easy "on their pans." This leads to a scuffle with police outside which lands the California delegates in jail for ten days. "That's nearly a week," says Stan. This is the kind of scene Hal Roach was partial to, and he's doubtless responsible for similar sounding material that was filmed for OUR RELATIONS (1936). The SONS sequence does not read like the kind of material that would have played well in the context of the film and was probably best excised as happened.

The jail sequence concludes on page 39 of the script. The written instrument was a work- in-progress because the final three pages are meant only as a synopsis of sequences to the finish of the picture. These begin with the wives discovering the boat has been shipwrecked. Stan and Ollie arrive home in a taxi full of pep. Nobody's home. They discover the newspaper and their supposed watery grave. Before they can leave, the wives arrive outside with a spiritualist (another story notion Roach was always partial to). Of course there is no seance in the film, but it was intended that the spiritualist would divine Stan and Ollie's fate by listening to a series of knocks.

"The knocks are answered unconsciously by Stan and Babe up in the attic trying to open a coconut or whatever the case may be," in the words of the script. The wives are cheered by knocks that signify their hubbies have survived the catastrophe. The ladies leave for the movies to kill time as they await the next bulletin. On the screen is a newsreel. One event happens to be "a shot of Mussolini, and Babe's wife makes a remark about how much her Oliver resembles him, that they both have that same powerful chin."

Roach had not yet met and entered a doomed partnership with Benito Mussolini, but just that spring he and Bob McGowan, travelling as mentioned in Europe, and driving an ostentatious rented open car which commanded attention, had returned Adolf Hitler's official salute from a motorcade blocking their exit from the Adalon Hotel in Berlin! Roach said Hitler couldn't help but notice their pretentious automobile, and "must have figured we were important characters!"

In view of the confusion over the roof sequence, previously covered, it's worth noting that the script, at least at that particular stage, intended one roof sequence only, at night, in the rain.

Stan and Ollie's interception by Harry Bernard, as the neighborhood cop, was not scripted. At least not in this version of the story. Instead the erring husbands are to spend the night in the rain, on the roof. It is at least possible that the daytime stills on the roof showing Stan and Ollie fully dressed are supposed to depict the morning after, when they are preparing to come down and face their wives with an alibi, but no daytime roof scenes were reflected in the script. Stills also exist showing them clad in their usual "business" suits, inside, downstairs, just before confessing all to the stone-faced spouses and getting the business themselves. As actually filmed, they confess in pajamas, which were soaking wet outside, but are miraculously dry moments later inside.

Back on the roof, as written, "Stan and Babe make their plans for the morning and we fade out on some gag," was the plot point. Next day the wives have breakfast and "take it big" when they spy their husbands outside "wetting themselves with a garden hose or maybe lying in the fish pond," preparing themselves to look like they have been shipwrecked. (The script provided no sequence showing how they got down off the roof in the daylight; a straight cut was called for to reveal them outside, in the yard.) Mrs. Hardy wants to go out and "murder" Babe right away, but Mrs. Laurel prefers to hear their story, first. Ollie, always so helpful, obliges.

"Stan is also trying to help put over the story but keeps saying the wrong thing," reads the text. As the boys conclude their alibi, a taxi pulls up outside with Ollie's brother-in-law, Bill. The story concludes, "Stan and Babe think that the brother is going to put the squeak in and they start to exit. The brother with a big smile says, 'We all met in Honolulu.' Stan and Babe take it big and get very hilarious, pretty nearly kissing the brother. This burns the wives to a crisp; they can't stand it any longer."

All of which was reworked and upgraded in rather remarkable fashion!

Candid stills exist showing the stars and writers at ease between scenes re-thinking the story, blocking out and polishing routines, adding gags, discussing what plays and what isn't working, and everyone, always, smoking.

Ollie to Stan in reel number six, SONS OF THE DESERT: "You little double crosser. If you go downstairs and spill the beans, I'll tell Betty that I caught you smoking a cigarette!"

Stan to Ollie: "All right. Go ahead and tell her. What do you think....Would you tell her that?"

Ollie: "I certainly would."

As usual SONS OF THE DESERT was shot pretty much in continuity. This allowed for spontaneous inspiration and improvisation of naturally developing story elements and gags which served the film well.

Setting aside Hal Roach's stormy plane ride to a convention, and whatever original concepts were invested by Frank Craven, it is curious that the script makes no reference to its partial antecedent -- Laurel & Hardy's silent two-reeler WE FAW DOWN, coincidentally released five years before SONS OF THE DESERT on the exact same date, December 29 of 1928. As mentioned, the reworking of the short's premise was so obvious that VARIETY mentioned the connection in its review. In WE FAW DOWN it's a poker game the wives disapprove of, and which the boys want to attend. And a movie theater burns down instead of an ocean liner sinking. But both calamities are disclosed to Stan and Ollie in newspaper headlines, and both films feature shotguns, knife-wielding and water drenchings.

To a lesser extent, SONS OF THE DESERT also vaguely reflects ingredients found in BE BIG (1931) but again there is no mention of that film, nor any specific tie to its story, in the SONS script. There is, however, one "inside" line actually spoken by Mae Busch in the last SONS OF THE DESERT reel when she says, "Oliver. I want you to be big. Bigger than you've ever been before. Are you telling me the truth?"

The titles of earlier Laurel & Hardy films turned up often enough again in subsequent efforts that their subtle reuse, such as in this instance, could not have been coincidental. Clearly the filmmakers were amusing themselves.

"Roach Feature In Box," was the headline for the single paragraph story in the October 24, 1933 edition of THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER. "William Seiter brought in the Laurel & Hardy feature at Hal Roach Studios five days ahead of schedule when the cameras finished grinding on SONS OF THE DESERT yesterday," the story stated. "Seiter returns to RKO, the studio from which he was borrowed about two months ago."

Following post-production work and at least two sneak previews, less than two months later SONS OF THE DESERT was ready for trade reviews at the Wilshire Theatre in Santa Monica.

From the resonance of WE FAW DOWN to Hal Roach's near ill-fated trip and convention, through the writing process, the gathering of talent on both sides of the camera, arranging financing, building the sets, finding locations, through the thousands of choices made, the shooting, posing for stills, the long night in wet clothes on a chilly rooftop, the bone-crushing slapstick, all the things which didn't work, the re-shooting, the bad case of Canus Delirous, the real-life marital troubles at home, at several homes, the distracting coverage by the press, on to the cutting, the scoring, the publicity, the previews, the re-cutting, the distribution, the premiere, the domestic and international releases....Through all this, the filmmakers on the little lot of fun in Culver City had successfully transposed an idea from script to screen.

What's more, their inspired work did and continues to bring smiles of recognition, hearty laughter, deep contentment and immense satisfaction to fortunate, delighted movie fans now and in the future, anywhere the film is shown, on video, on television, or best of all, in one of those darkened movie palaces with a huge audience and a sparkling, theatrical density 35mm print.

Mrs. Hardy to Ollie in reel number seven, SONS OF THE DESERT: "Have you anything else to say?"

Ollie to his wife: "Why, no. That's all there is. There isn't any more. Is there, Stanley?"

Stan to Ollie: "No. That -- that's our story and we're stuck with it...in it...."